By Laurel Busby

Staff Writer

A decade ago, Marci Crestani took up woodworking. It wasn’t easy. She enrolled in a woodworking program at Cerritos College, but she struggled with her ability to visualize projects in three dimensions, which made designing and building pieces challenging.

“I was the worst one in the class—hands down,” said Crestani, 63, who noted that she was also intimidated by the unfamiliar, large, and loud machinery. Plus, she was one of only a few women in the program at that time.

But the Palisadian kept at because the teacher was funny, but also because a teaching aide took her under his wing. He told her, “You can do this. Don’t worry. It’s not that difficult. You’re overthinking things and you’re too scared.”

She worked through her fears and still takes independent lab classes at the school, which now has a large number of female students and provides her and other students with “an incredible sense of community.”

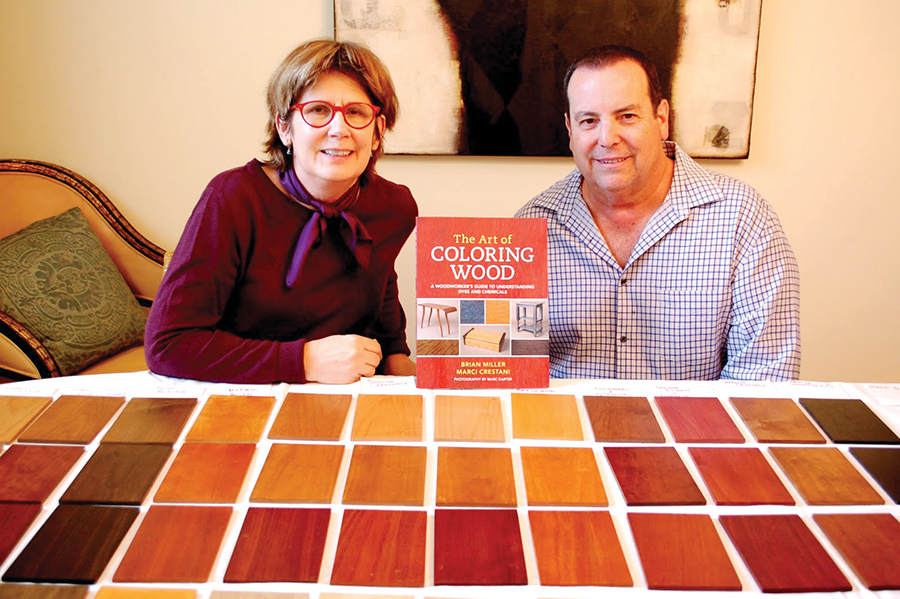

In fact, Crestani, a Chicago native whose husband, Bob, is an entertainment executive, has since created a prize-winning piece that took the People’s Choice Award at the Yosemite Renaissance Art Exhibit, and another project, a table that seems to channel the spirit of a fragile deer, was chosen to illustrate the cover of the book,The Art of Coloring Wood, which she recently co-wrote with one of her teachers, Brian Miller.

The two took on a subject that most people, even skilled woodworkers, often know little about. In fact, the last book on the subject was published about 30 years ago and didn’t give any formulas for making dye preparations.

Coloring wood means using chemicals and dyes instead of stains to finish wood. Dyes dissolve in water and become one with the water and eventually the wood, which allows light to penetrate the wood and illuminate the grain in unique ways. Stains are more like a salad dressing with little particles that always stay separate, so the pigments sit on top of the grain and don’t allow light to penetrate it.

Using chemicals and dyes instead of stains, “you can achieve depth of color, but with great clarity,” Miller said. “You don’t sacrifice the grain of the wood.”

To explain the subject and show how dyeing can enhance woodworkers’ projects, the two spent many days together at Crestani’s Alphabet Street home, coloring six types of wood (alder, cherry, maple, mahogany, oak, and walnut) with various chemicals and natural dyes. The book is full of photos of how the various coloring agents look on the wood samples, which may range from a light or gray hue on maple to a deep reddish brown on mahogany.

These variations occur in part because of how a compound in the wood, tannic acid, reacts with the dyes. Maple has no tannic acid so unless tannic acid is added, the wood doesn’t react with the dye. While oak, which has a high level of tannic acid, will have a much deeper color change.

“The thing I find interesting,” Crestani said, “is that chemicals need an organic substance, tannic acid, in order to do their magic.”

“Otherwise they just deposit their own color to the wood,” said Miller, noting how slight such coloring can be.

Crestani added, “Plant and insect and organic things that you use to color wood need chemicals to fix them to the wood. There’s a mutual dependency. If you’re doing chemicals, it helps if there’s an organic thing, and the natural dyes need the chemicals too.”

Some of the chemicals can be a little intimidating to novices, so the book explicitly lays out the safety requirements. For example, certain chemicals, such as ammonium hydroxide and potassium dichromate, require special handling, such as gloves, eye protection and respirators.

Natural dyes, such as logwood extract—from the heartwood of a tree—and cochineal, which comes from an insect, also often use chemicals called mordants to bind the color to the wood. So even with natural dyes, chemicals, most commonly ferrous sulfate, alum and potassium dichromate, are frequently used.

However, there is a dye option for people who want to avoid any toxic substances. Synthetic dyes, which can be used on children’s toys or food dishes, are non-toxic. The downside is they aren’t as light fast, so they aren’t ideal for outdoor applications. Chemicals also produce more color variations, lend an aged look to the wood, and provide more clarity than dyes.

Regardless of the wood-coloring choice, generally a clear coat finish will be applied, so the color will be sealed under the finish.

For Crestani, who has two sons, John, 30, and Nick, 27, and one grandchild, the process of working with Miller on the project was fascinating. She learned about the history of dyes, which have been used throughout the world for centuries and were often closely guarded secrets, some of which Miller has been able to ferret out.

For example, Charles and Henry Greene of the Arts and Crafts movement often used ferrous sulfate and potassium dichromate to color their houses, including the Blacker house, which Miller helped restore in Pasadena. He discovered their preference by sending a sliver of wood in for testing and then experimenting with the chemicals that were uncovered.

Throughout their process, Crestani gained more experience with coloring wood.

“It’s actually not hard to do, but it can be intimidating,” said Crestani, who moved to Pacific Palisades 26 years ago. “You feel like you’ve just made this beautiful thing, and you can wreck it so easily.

“It’s taken however many months to make something and you can just wreck it in an hour,” she said. “You really have to learn about the application.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.